False Amnesty

William Wannukhow and his sons were settled back in Magunkaquog in June of 1676 when the Massachusetts General Court promised protection to Praying Indians who delivered themselves to the English. Wannukow was encouraged by Annaweekin’s brother, James Printer, to seek English protection, which they did in August of 1676. Despite the promise of amnesty, they were soon apprehended by the constable to answer for their participation in the raid on the Eames house. There was no amnesty, the three men were sentenced to death and hanged on Boston Common September 21, 1676.

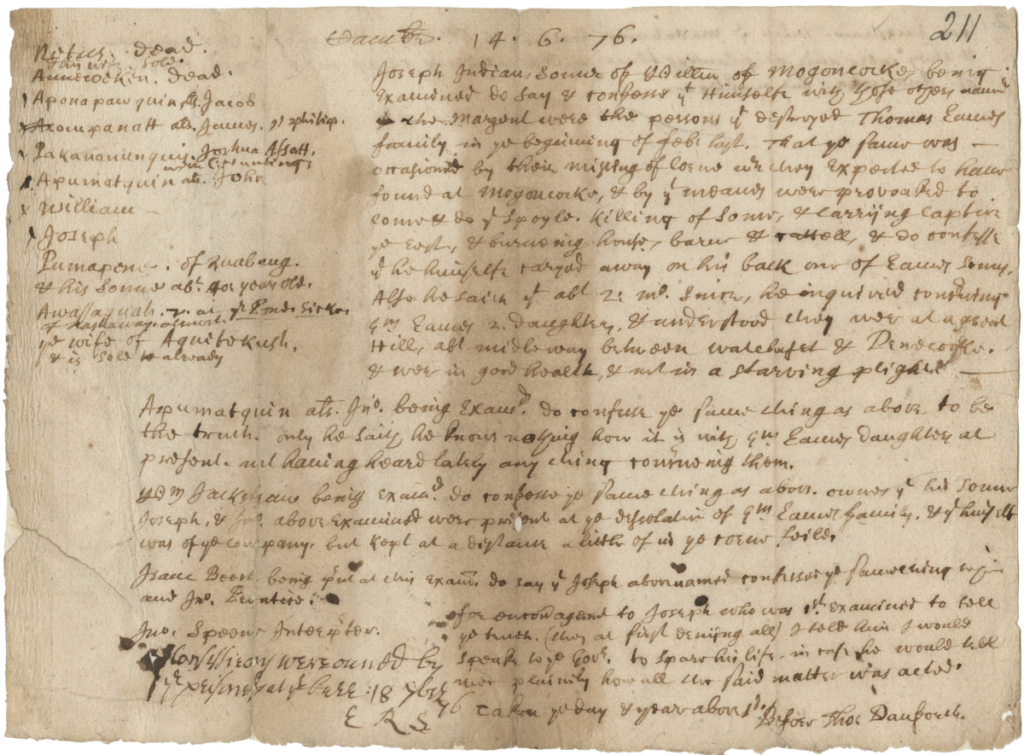

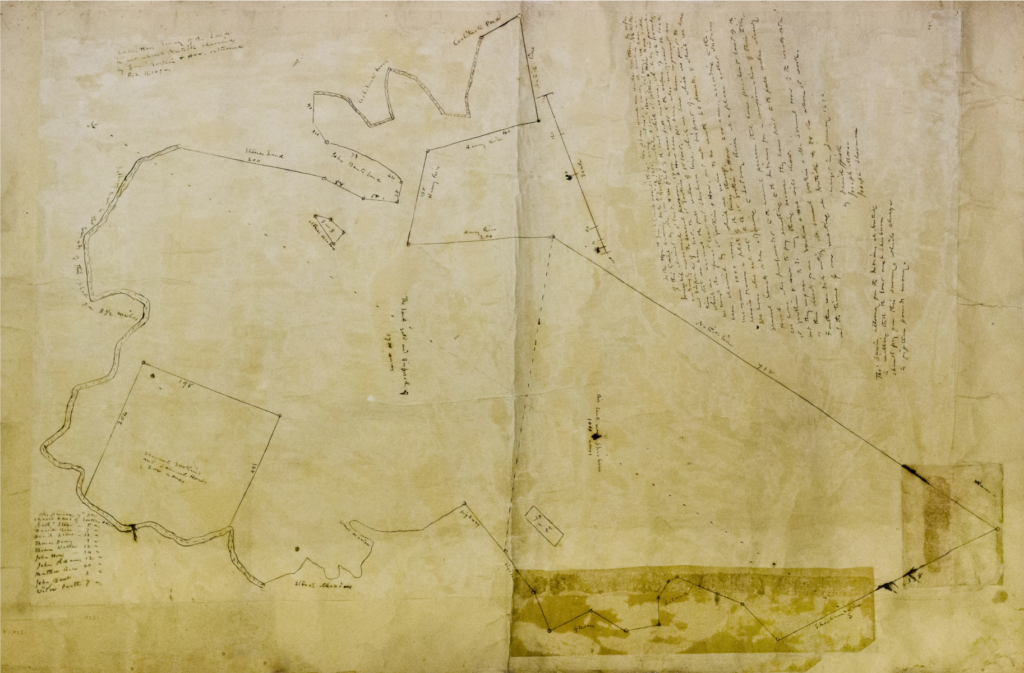

Examination of William Wannukhow and Sons by Thomas Danforth, 1676

Courtesy Massachusetts State Archives

Thomas Danforth examined William Wannukhow and his sons Joseph and John while they were imprisoned in Boston. At the bottom of the document, Danforth writes “For encouragement to Joseph who was 1st examined to tell that truth (they at first Denying all) I told him I would speak to the Govr to spare his life in case he would tell me plainly how all the Said matter was acted.”

The aformentioned petition which Wannukhow and his sons submitted to the court after this examination referenced the multiple promises of clemency that were made to them over the course of this time.

Click on the document to read a transcription.

This amnesty bait-and-switch was the fate of many English-allied Native People as the war came to a close. Tantamous was among 200 individuals who turned themselves over to the English under the guise of amnesty negotiated by Tantamous’s son, Hantomush (Peter Jethro). Upon doing so, Tantamous was imprisoned and marched to Boston, where he was hanged on the Common September 26, 1676. Peter Jethro was painted as a villain by English contemporaries who claimed he turned his father over in cold blood, but evidence indicates that Peter genuinely believed that he had secured amnesty for his kinsmen.

The war came to Framingham one more time in June of 1676. Tom Wuttasacomponum, an English ally and captain in the militia, was settled openly with other Praying Indians on a hill straddling modern Framingham and Natick. Wuttasacomponum had escaped Metacomet’s allies and was hoping to make contact with the English to assert his alliance when English scouts encountered the group and instructed them to report to the Garrison at Marlborough. Upon arrival, Wuttasacomponum was immediately taken prisoner and charged with participating in raids at Medfield and Sudbury. Despite a lack of evidence, he was sentenced to death and hanged on Boston Common.

The hill on which Tom Wuttasacomponum was taken captive still bears the name “Captain Tom’s Hill.”

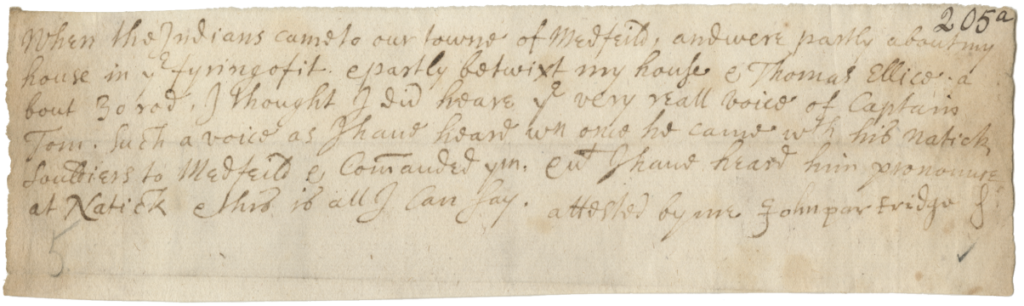

Testimony Against Captain Tom by John Partridge, 1676

Courtesy Massachusetts State Archives

This testimony regarding Captain Tom’s participation in the raid at Medfield given by John Partridge hinges on the claim that during an active raid, about 30 rods (165 yards) away from his home, Partridge “thought [he] did heare the very realle voice of Captain Tom,” a voice he had heard only a few times.

It is telling that such vague testimony was enough to condemn a Native man who, until months prior, was a respected ally and the leader of an English-style militia.

“I accompanied him to his death; on the ladder he lifted up his hands and said, I never did lift up hand against the English, nor was I at Sudbury, only I was willing to go away with the enemies that surprised us. When the ladder was turned he lifted up his hands to heaven prayer-wise, and so held them till strength failed, and then by degrees they sunk down."